Strathavon is a real place!

Although the characters and events in the novel, The Blood And The Barley, are all fictitious, the actual place itself, the glen or to be more accurate, the strath, is very much a real place. Strath is a Scots term meaning wide river valley of flat relatively fertile land bounded by hills. Strathavon, therefore, is the valley of the river Avon, pronounced A’an, Avon being the anglicised form of the Gaelic Abhainn, simply meaning river or stream. From the same Celtic root, we have the Welsh word afon, also meaning river.

The river Avon has its source in Loch Avon nestled between the summits of Cairn Gorm and Ben Macdui, the second highest peak in the British Isles. Associated with Ben Macdui is the mythical creature Am Fear Liath Mòr, which I mention in the book. The great grey man of Ben Macdui is said to haunt the mountain’s summit and resemble a Yeti. The first documented and highly intriguing encounter with this phenomenon was in 1891 by the eminent professor J. Norman Collie, a highly respected scientist and mountaineer, although there had been many verbal accounts.

Alone on the mountaintop in a thick mist, he heard the loud crunch of footsteps behind him but could see nothing in the mist. The footfalls did not follow his own but occurred for every three or four steps that he took. To the professor, it sounded as if someone was walking behind him but taking steps three or four times the length of his own. When he stopped, the eerie crunch also stopped and began again when he did. As he walked, the crunch, crunch, began again, and he was seized with terror and blundered blindly down the mountainside for four or five miles to the safety of Rothiemurchus Forest. It was only after the professor spoke openly of these events at a meeting of the Cairngorm Club that other eminent mountaineers came forward to tell their extremely similar accounts. Again, they heard the crunch of footsteps but not in time with their own, they seemed to belong to a giant, invisible in the mist. When local gamekeepers and stalkers were asked what they made of all this, they looked grimly at each other, then muttered that they did not speak about it. This is the creature I have Hugh McBeath so afraid of.

The river Avon is almost entirely contained within the Cairngorms National Park, draining the north-eastern sector of the Cairngorms, collecting headwater from many gushing streams and burns along the way, then flowing east through Glen Avon. At dramatic Inchrory it veers north toward Tomintoul (my Balintoul) the highest village in the Highlands, and then roughly north past the Cromdale hills to the ruins of Drumin Castle, where it joins with the river Livet. Glenlivet is the neighbouring glen with its world-famous distillery which also began as an illicit smuggling operation.

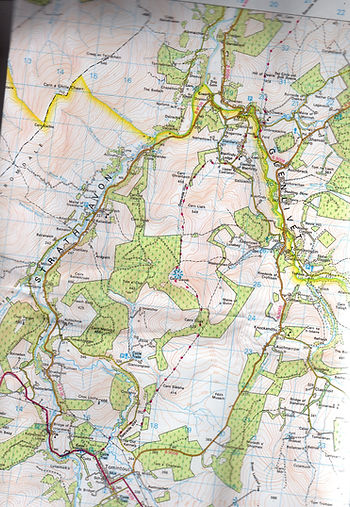

The yellow line marks the boundary of the Cairngorms National Park with Strathavon to the left.

The stretch from Tomintoul to Drumin is where the novel is set. Less barren and dramatic than the higher reaches, this area was home to many families of crofters, herdsmen, and clansmen, all tenants of the Duke of Gordon, known as The Cock o' the North. Clearly inhabited since ancient times, the land here is strewn with evidence of their early presence, and something of their beliefs. Ring cairns, standing stones, Pictish symbol stones, cairns, ruined castles, towers, and keeps litter the landscape, all rich fodder for the imagination. This is the land of my ancestors on my mother’s side, my mother and grandmother were both born in Tomintoul, and I have always loved it here. In the past it was a remote, hard-to-reach place, cut off from anywhere and a stronghold of the Catholic faith, perhaps due to historic protection from the Jacobite supporting Dukes of Gordon. Today, it is still a relative backwater, not on the tourist map, thankfully perhaps. Sir Henry Alexander (1846-1928) explorer and plant collector, said of Strathavon:

‘Regarded from the point of view of river and mountain scenery, this is perhaps the most perfect glen in Scotland. For in the whole 38 miles from its source above Loch Avon, to the Spey, there is not a single dour passage, and every phase of highland landscape is presented. From the wild barren grandeur of Ben Macdhui to the luxuriant beaches of Delnashaugh, under whose shade the river flows deep and dark to meet the Spey. It is rash to discriminate among the beauties of such a glen, but perhaps not the least attractive are those in the middle reaches, where the hills are friendlier rather than fearsome, where groves of silver birches break and soften the valley side, where the alder dips its branches in the singing water, and where the oyster-catcher sweeps and cries above the shingle.’

It is in these middle reaches that I have set the saga, for I cannot agree with Sir Henry more. The landscape here has an ancient, forgotten feel as if it still holds many mysteries and is loath to give them up. It was a stronghold of whisky smugglers for centuries, most especially in the 18th and early 19th century. No longer owned by the Dukes of Gordon, the land now comes under the administration of the Glenlivet Estate and is owned by the crown. It passed to the crown from the Duke of Gordon and Richmond in 1937 in lieu of death duties.

Strathavon in early April, still a wintery scene. Photo Angela MacRae Shanks.

Kirkmichael Churchyard, where my great-grandfather is buried with a great many of his kin. Photo Angela MacRae Shanks.

Below is the packhorse bridge over the river Livet, used by smugglers from Strathavon and Glenlivet to smuggle their mountain dew out to thirsty buyers. This was a remote and inaccessible area and the climate was harsh (the Cockbridge to Tomintoul road is still generally the first to block with snow every winter). Following the disaster of Culloden and the Government’s concerted efforts to make certain there could be no more Highland risings or support for the Stuart cause, distilling and smuggling whisky became the only way for these tough Highland people to survive. Rents rose steeply and land suitable for growing anything beyond subsistence crops had always been scarce, so whisky, the currency of the

glen, became the way to survive. Today there are still three legal distilleries, including the famous Glenlivet, in the area.